Life 4.7 Million Years Ago | How Did Prehistoric Humans Survive to Sustain Life?

The dry earth crackled beneath bare feet. A scorching sun loomed over the East African savanna, casting long shadows across acacia-dotted plains. Life 4.7 million years ago was not just primitive—it was perilous. And yet, in this raw, untamed wilderness, our earliest human ancestors—hominins—took their first fragile steps toward survival, adaptation, and, eventually, civilization.

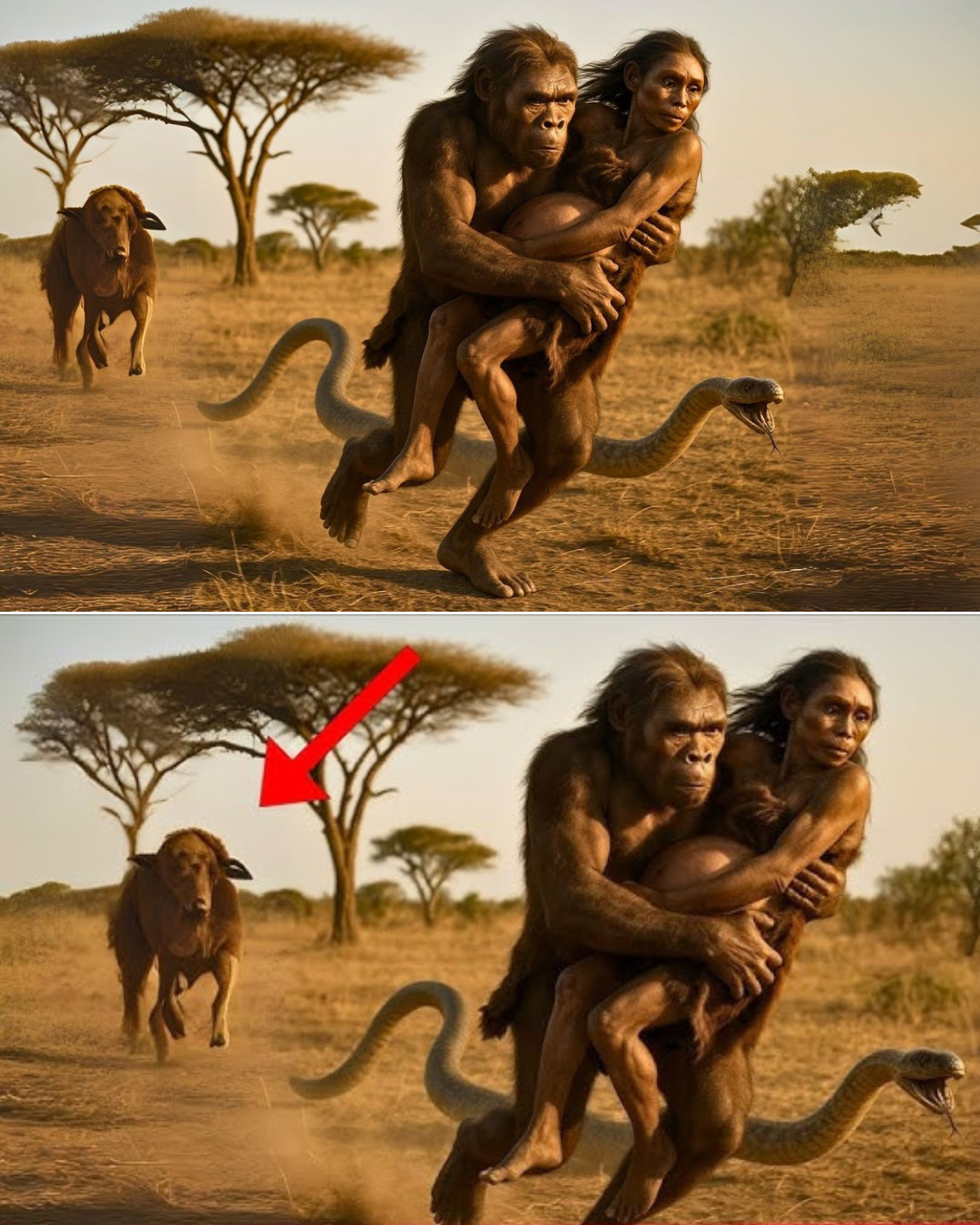

In this prehistoric era, survival was not a guarantee—it was a daily battle. These hominins, likely Australopithecus afarensis or a closely related species, were not the top predators of their time. They lived in a world dominated by saber-toothed cats, massive constrictor snakes, hyenas, and scavenging birds with wingspans wider than a modern car. Food was scarce, predators were relentless, and the rules of existence were brutally simple: adapt, flee, or die.

But adaptation was their superpower.

Despite their physical disadvantages compared to larger, faster predators, early humans had something unique: an evolving brain. This gave them an edge in decision-making, communication, and—most importantly—cooperation. They formed close-knit social groups, which offered not only emotional bonds but tactical advantages. A pair of eyes could spot danger. A group of eyes could form a strategy. The roots of community, empathy, and protection were planted in these desperate moments of survival.

Imagine a moment like the one shown in the dramatic image above: a male hominin lifting a mate to safety, leaping through dust and fear as a venomous snake coils in strike position and a predator charges in the background. These were not isolated events—they were daily realities. Each movement, each decision, could mean the difference between extinction and endurance.

But survival wasn’t just about escape—it was about adapting to the environment.

Early humans began using rudimentary tools. At first, it was sticks to dig for roots or stones to crack nuts. Eventually, they discovered sharp-edged rocks that could scrape hides, butcher meat, and defend against threats. These tools didn’t just give them access to new food sources—they gave them more time. Time to learn. Time to evolve. Time to survive.

Their diet was opportunistic and diverse. They foraged for berries, tubers, insects, and occasionally scavenged meat left behind by larger carnivores. They learned to read the landscape—to recognize safe paths, to avoid predator territories, and to migrate with the rhythms of nature. Water holes, shaded groves, and hidden caves became their sanctuaries.

Mothers passed knowledge to children—not through words, but through gesture, imitation, and sound. The roots of language began here: in the urgent warning grunts of danger, in the soothing hums of reassurance, in the joyful exclamations of success. Over generations, this vocal communication evolved into something more complex and powerful, laying the foundation for human culture.

Social bonds became essential. Raising offspring required collective care. Injured members were sometimes protected and nursed—an extraordinary act rarely seen in the animal kingdom. This wasn’t just survival. It was the birth of compassion.

And while the dangers were many, they also provided the pressure needed for growth. The constant threat of predation honed their senses. Their upright gait—initially an adaptation for moving through trees and across open land—allowed them to travel vast distances, to carry tools and infants, to explore and escape. It also freed their hands, opening a world of possibility: from holding weapons to building rudimentary shelters and shaping the environment.

Climate, too, played a pivotal role. Shifting weather patterns meant shifting resources. Droughts forced migration. Floods reshaped territories. In this ever-changing ecosystem, those who could adapt not only survived—they began to thrive.

By living in groups, early humans learned the strength of cooperation. They began to share food, roles, and responsibilities. Some gathered, others guarded. Those who couldn’t hunt could still teach. Slowly, they carved out a space in a hostile world where survival wasn’t just possible—it was repeatable.

Over time, fire would come. And with it, warmth, protection, cooked food, and eventually the birth of myth and meaning. But in these earlier epochs, life was raw, unscripted, and uncertain. Each sunrise brought danger. Each night brought predators. And yet, through resilience, ingenuity, and connection, prehistoric humans endured.

The scene depicted here is more than artistic imagination—it reflects the essence of our journey. It reminds us that everything we are today—our technologies, cities, philosophies—began in moments like these: where instinct met ingenuity, where love met danger, where the will to survive sparked the future of our species.

These ancient ancestors were not “less evolved” versions of us. They were pioneers—navigating a world we can barely imagine, forging bonds under threat, and crafting the early chapters of human history not with ink, but with courage, grit, and survival.

As we look back 4.7 million years, we’re not just seeing ancient beings—we’re seeing ourselves in the earliest mirror. We’re witnessing the spark that led to everything: fire, language, culture, civilization.

Their survival was the beginning of ours.